Jacob Stein

Blockchain Case Use 1: The IBM Food Trust

Blockchain has, at the time, become a buzzword in a sense. This is because of its tight association with the larger buzzword 'cryptocurrency.' Cryptocurrencies and NFTs are only enabled by public blockchain technology, which thus creates an undeniable link between them. Cryptocurrencies have a deserved negative reputation because of the rife scams, ostensible worthlessness, complexity, and extreme volatility. Blockchain inherits this reputation by extension, and is consequently overlooked as a practically-applicable technology. This, in my opinion, is the greatest tragedy of Web3, and may delay the legitimate development of blockchain technology for a long time. I personally believe the technology is here to stay, despite the valueless projects spearing its spread. My goal is to explore some of blockchain's more practical uses, and hopefully change the narrative for a few people.

Cryptocurrencies are built on public decentralized ledgers. This means all actions and transactions on the blockchain can be publicly observed and traced under pseudonymous identifiers. This has practical use for creating any automated process that is governed by script rather than a central authority. Cryptocurrency is the first implementation of a public blockchain, and does a strong job demonstrating its purpose. They are meant to simply function as a currency without the regulation of a potentially incompetent central bank, simple enough. Blockchains, however, can be utilized by central institutions to bolster security, automation, and speed in pretty much any workflow. This series is meant to identify both current and potential workflows that are being improved with blockchain technology.

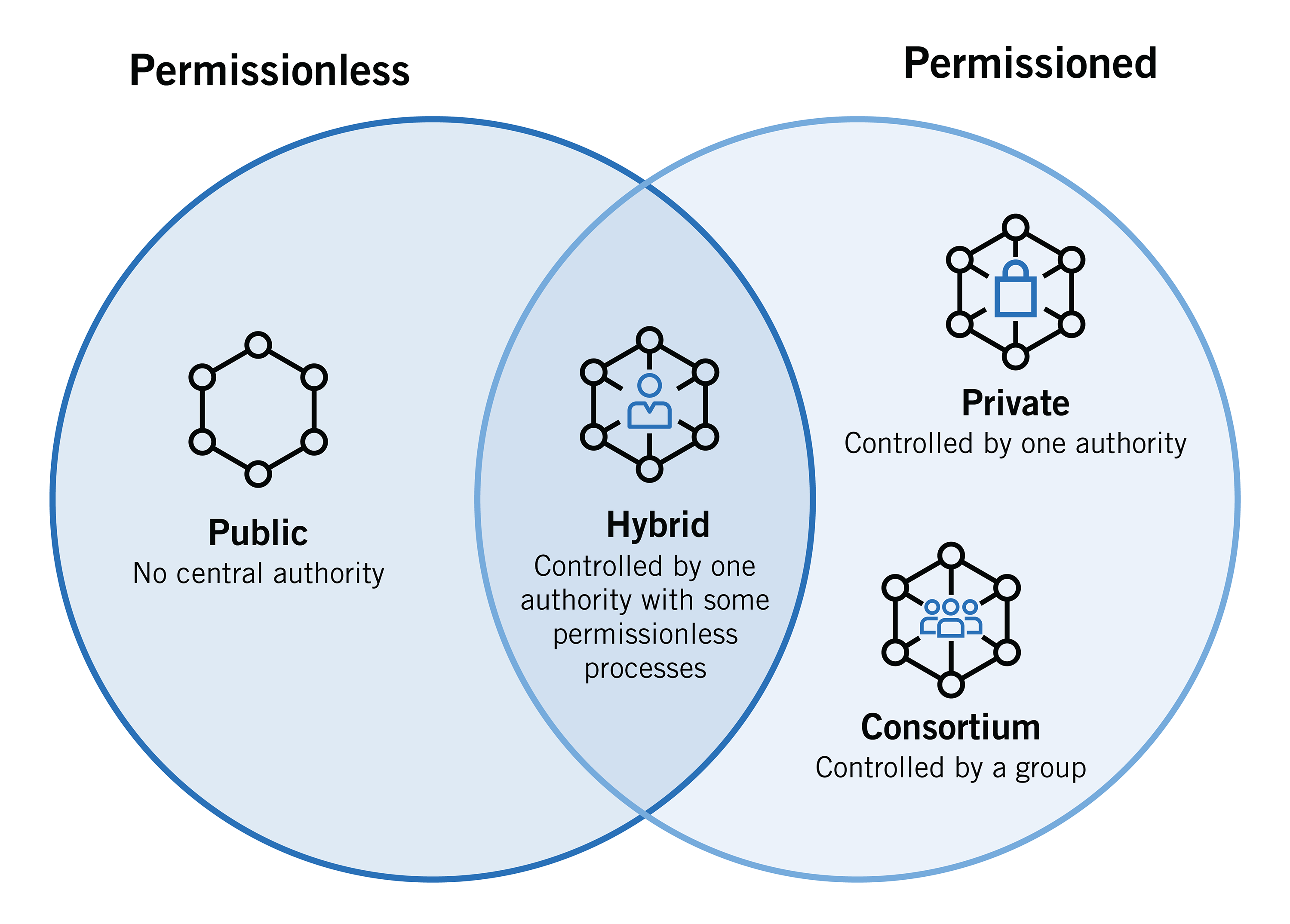

For obvious reasons, businesses and governments do not want data stored on a blockchain to be publicly available. The solution to this is permissioned blockchains. Public blockchains are permissionless, meaning anyone with a computer and Internet connection can join the network, either as a user or node. On a permissioned blockchain, access and functionality is dictated by a central authority or group of entities. These two types of blockchains can be further sub-divided, by the general difference in access is the most important point.

While blockchain and Web3 enthusiasts may ascertain that decentralized blockchains are the future, it is larger entities that will truly develop the technology. Companies will generally use permissionless blockchains to develop their service, and we will dive deeper into one company's implementation right now.

The IBM Food Trust is a consortium of entities involved in the food supply chain using blockchain technology to enhance communication, transparency, speed, and security. The Food Trust is built upon IBM's own IBM Blockchain Platform (which is a whole other story), which is built upon Hyperledger. Hyperledger is an open-source project managed by the Linux Foundation with the goal of enabling blockchains for enterprises. This string of relational building is not particularly important, whereas it is more important to focus on how and why IBM is using the technology with the Food Trust.

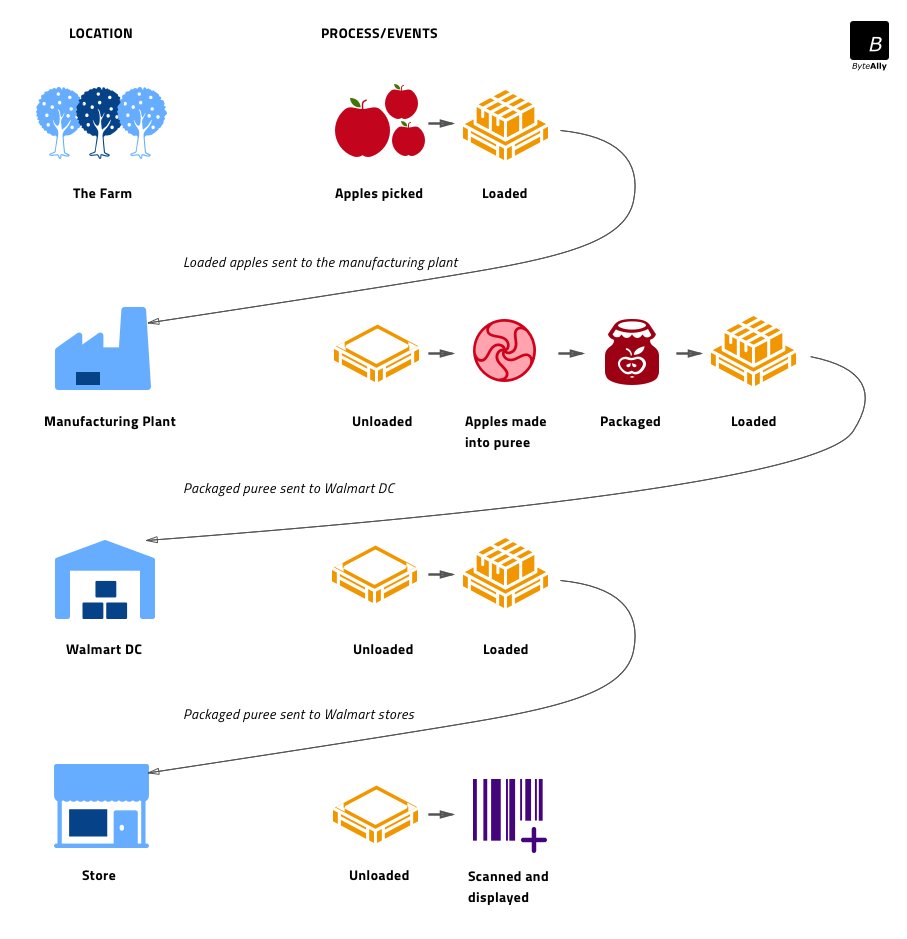

Imagine you go to a local Walmart looking for apple puree. Now, think about the process that went into getting the puree from a tree into your local Walmart. See the diagram below provided by the Food Trust.

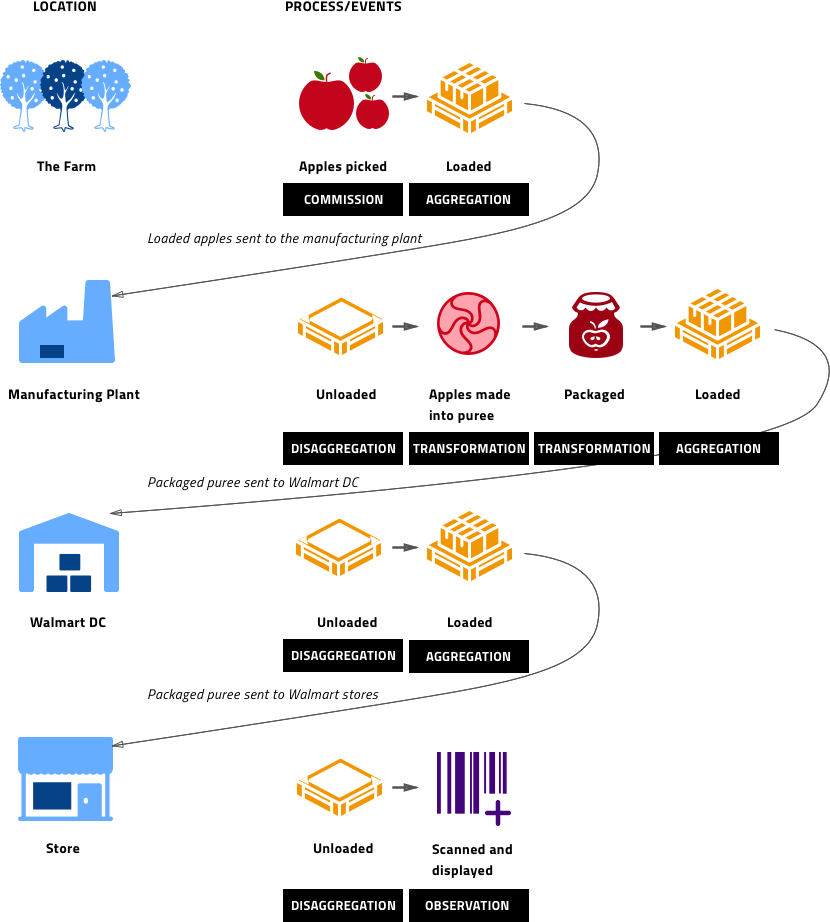

According to documentation provided by the Food Trust, events within the supply chain are then broken down into six categories:

Commissioning: the initial creation of a product

Deletion: the end of a product

Transformation: the irreversable transformation of the product

Aggregation: the grouping of multiple products together

Disaggregation: the ungrouping of multiple products

Observation: the observation of a product

By standardizing events within the food creation process, companies can navigate and track progress with greater ease. Here is how these titles are applied to the apple puree diagram from above.

Entities involved with each step track any events that happen as the food moves through, and compiles them into an XML file, a format for storing data. IBM stores the data according to the GS1 EPCIS standard, and then companies are ready to share information on their EPCIS events.

Before any entity begins sharing their events, they first share their master data with IBM. This includes their primary locations (farms, warehouses, etc.), and generalized item data (weight, SKU number, etc.). Entities can then set their visibility level to one of four standards set by IBM:

Open: data is visible to all entities within the Food Trust

Restricted: data is visible only to you and immediate trading partners

Linked: data is visible to all organizations that are part of your supply chain

Private: data is visible only to your organization

To sum up so far how entities can engage with the Food Trust: companies register with the Food Trust, categorizing their part of the process into six distinct phases. The entity registers their master data and compiles their phase information into XML files, which are then converted according to the EPCIS standard. The entity can then permission who can see their information, and then begin sharing there data. With this process in mind, we can now explore why any company would go through these steps, along with the larger benefit that it has.

The actual IBM Food Trust interface contains a variety of tools for companies to use. Unique to the Food Trust is its traceability. According to their documentation: "In a transparent and secure network, you can gain visibility upstream or downstream, view location or status, and verify credibility or safety. The Trace module enables effective management and food safety across your entire food system." Next up is documentation. Documents can be uploaded, managed, edited, and shared across a company's permissioned network. The documents themselves are also entirely traceable, and can be easily authenticated. The plethora and interconnectedness of information also allows for unique data insights on a built-in module that other platforms may not be able to provide. The insights module can be used to "gain deep insights into supply chain efficiencies, analyze in seconds where and how your fresh product is spending time with inventory flow, average dwell time, time-since-harvest, and more." Additional informatics can be tied in using available APIs.

Enthusiasts love to tout blockchain's decentralized sub-genre because of the perceived social benefit they provide rather than being curated to corporate interests, as a permissioned one may be. Under the right circumstances, however, the corporate benefits provided by expedited workflows can extend to create a larger social benefit. This decision, however, falls on the shoulders of corporations, which is a concerning reality given their track record. The IBM Food Trust, for example, can cut production costs, increase efficiency, and provide security for participants. These factors simultaneously increase revenue in cut costs, which leads to more profit. This profit increase could be balanced out to reduce food prices across the board (the social benefit), or to line the pockets of executives a bit more. If you want to discuss politics though, go to the politics section. Let's now explore the systemic benefits that blockchain brings to the food supply chain.

Increased Supply Chain Efficiency

Food supply chain inefficiency is an easily identifiable problem made evident by the COVID-19 pandemic. Inefficiences can have negative implications for consumer prices, carbon footprint, food waste, and freshness. Inefficiencies exist because of the outdated management systems maintained by portions of the chain. Some entities still rely upon manual processes that can make it very difficult to take inventory and identify problems. These entities are also slow to adopt emerging supply chain technologies, if at all. Such conditions lead to poor coordination across the chain as a whole. The chain is only as strong as its weakest link. The Food Trust allows for involved entities to work across a shared ecosystem, making identifying bottlenecks via traceability an easy process. The availability and provenance of such information also allows for companies to construct informed forecasting models, and change their contracts accordingly in anticipation of any projected changes. Such a system is also built to expand, making the addition and integration of new participants an easy task.

Brand Trust

Now more than ever, brand construction and recognition is important. Consumers are more likely to buy food from companies that are identifable as sustainable-conscious. This is prompting companies to strongly adhere to generalized regulations, as well as to develop their own sustainability adherence programs. Quality and safety are factors that will draw and keep consumers around a brand. By nature of the technology, blockchain allows for full and complete transparency, allowing companies employing sustainable practice to provide substance to their word. By being able to track the entire process, nobody can question the safety, authenticity, and care put into food production by a company. This transparency is what builds a strong brand.

Compliance Confidence

Every company knows that safety and regulatory compliance is a must, because the cost can be devastating. Food safety recalls have an enormous upfront cost for companies, compounded by indirect costs such as lawsuits, penalties, lost sales, and brand damage. The amount of loss at risk necessitates an airtight monitoring system to take preventative actions against circumstances that may warrant a recall. Existing supply chains, however, are not equipped to track and identify vulnerabilities. The ease with which companies can trace and identify problems using the Food Trust siginificantly reduces the risk of a recall, and if there is a problem, it will be caught before it takes a toll.

Enhanced Sustainability

Sustainability has not become an imperative for food companies. Most consumers are willing to switch their buying habits to remain environmentally conscious. The cost of unsustainable practices is mounting, both within the pockets of companies and on the environment. Sustainable food practices are no longer negotiable, especially with the projected population growth we will experience in the next few years. Using blockchain, farmers and other entities can share immutable documentation, audits, and certificates proving their ethical practices. Transparency and traceability across the chain also ensures that the incentives for sustainable practice are higher than ever, as actions will be public.

Improved Safety Monitoring

Along with sustainability, food freshness has become another non-negotiable issue for companies. People want fresh food on their plates, both for their conscience and personal health. As it stands, food usually visits a multitude of countries before arriving on a plate, and spends an egregious amount of time in transit. Food also becomes hard to track in transit, making it difficult to ascertain its freshness. As with other problems, this can be solved with blockchain's transparency and traceability. Companies can see where there food comes from, and only engage with entities that uphold the level of freshness that they desire. Transactional data also allows company to fully understand the state of the food when it comes to their stop on the chain.

Fraud Prevention

Food fraud is a surprisingly profitable industry, raking in billions of dollars a year around the globe. Fraudsters can exploit vulnerabilities and a general lack of oversight to peddle products that may be lacking the regulation they need. Both overly complex and outdated supply chains have a difficult time tracking fraud, as it can oftentimes be easily disappeared within the process. It is very difficult to falsify and confirm information on the blockchain. The provenance of that information is also traceable. Furthermore, blockchain encourages cooperation, and entities are unlikely to defraud their close organizers.

Reduced Waste

Hundreds of millions of tons of food go to waste each year across the world. Actions to reduce food waste are underway, but lack substance and organization. This is because reducing food waste is a systemic challenge, and requires cooperation and information from across the supply chain. Additionally, consumers are tossing out more and more food because of doubts surrounding freshness. Food waste is a textbook example of a problem that blockchain can help solve. Traceability allows supply chains to identify where and why food is going to waste, and remediate the issue. The sharing of data and general collaboration also encourages the creation of standards and procedures to reduce waste across the board.

I hope that this post has to any extent helped you understand how blockchain technology is actually applicable in real life, and the enormous impact it can have. I hope to create similar posts that explore how the technology can be employed in other scenarios, stay tuned.

Jacob Stein

Hello! I'm a junior at Boston University studying computer science and political science. I have a strong interest in blockchain technology use-cases and implementation. This blog is just meant to document and explore my areas of interests. Feel free to comment, or contact me at jmstein@bu.edu.